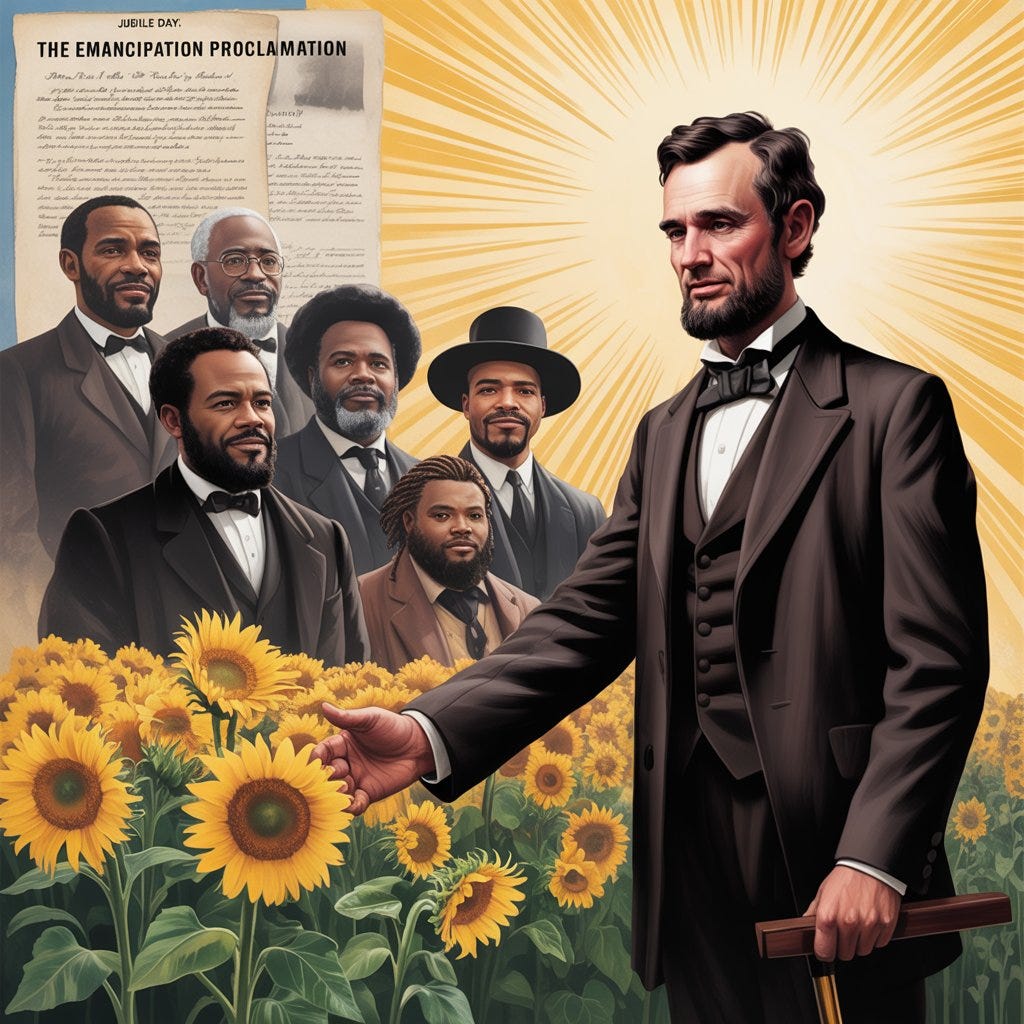

Emancipation and Freedom Go Hand In Hand

A Biblical perspective on Juneteenth, Christian Leadership and the long road to liberty

“The Spirit of the Lord God is upon me, because the Lord has anointed me to bring good news to the poor; he has sent me to bind up the brokenhearted, to proclaim liberty to the captives, and the opening of the prison to those who are bound (Isaiah 61:1).”

America is the land of the free and home of the brave. We are nearing our 250th birthday in 2026, as we celebrate our 249th Independence Day this year. It is a time for choosing once again. The USA began as a haven for persecuted Christians, grew through war and immigration, and remains a beacon of liberty to the world.

Our forefathers established a Constitutional Republic, and we must fight to keep it free. We invite people to visit, but we cannot open our doors to the world. We can show everyone what freedom and justice look like if we honor our heritage. The best way to encourage freedom around the world is to maintain it here.

The Civil War remains a hot-button issue. But recognizing the end of slavery in America is a worthy event, if we view it more broadly in our commitment to freedom.

The winter of 1865 marked a constitutional watershed that would echo through the corridors of American history. On January 31, Congress passed the Thirteenth Amendment, forever abolishing the peculiar institution of chattel slavery. After the end of the war between the states that had stained the republic's land for years, America needed to put bad blood behind us. Yet this legislative triumph, ratified by year's end, represented not the culmination of America's struggle with racial division. It was merely the opening chapter of a protracted moral reckoning that would test the nation's Christian character for generations.

The practical liberation of four million enslaved souls reached its crescendo on June 19, 1865, when Major General Gordon Granger proclaimed freedom in Galveston, Texas—the most remote outpost of Confederate resistance. This moment, immortalized as Juneteenth or Jubilee Day, fulfilled Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation in its final theater. General Order No. 3 declared that "all slaves are free" and established "an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves."1 While I prefer the name Jubilee Day, the portmanteau "Juneteenth"—blending June and nineteenth—captures the vernacular of freed African Americans. And, it happens to be another holiday in the summer months that gives us more time to enjoy the sunshine together.

The Architecture of Constitutional Justice

The Reconstruction Amendments formed a trinity of constitutional changes. The Fourteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868, granted citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the United States (not birthright citizenship or anchor babies), explicitly overturning the Supreme Court's infamous Dred Scott decision. The Fifteenth Amendment, ratified in 1870, prohibited the denial of voting rights based on "race, color, or previous condition of servitude."2 These amendments represented what historian Eric Foner termed "America's unfinished revolution"—a legal framework that promised equality but required moral courage to implement.3

As Frederick Douglass astutely observed in 1865, true freedom demanded more than legislative decree. "All I ask is, give him a chance to stand on his own legs! Let him alone," Douglass proclaimed. "If you see him going into a workshop, just let him alone, your interference is doing him a positive injury."4 This philosophy of dignified self-determination would become the cornerstone of African American leadership in the post-emancipation era. This is the same stance that conservative black leaders are taking today, attempting to instill more self-reliance in black communities.

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing slaves by their owners. The theological implications of emancipation reverberated through Christian communities, North and South. For many believers, the abolition of slavery represented the fulfillment of biblical justice—the year of jubilee proclaimed in the Bible, “Consecrate the fiftieth year and proclaim liberty throughout the land to all its inhabitants. It shall be a jubilee for you; each of you is to return to your family property and to your own clan (Leviticus 25:10).” The Methodist Episcopal Church, which had split over the issue of slavery in 1844, began the painful process of reconciliation. Baptist congregations, particularly in the South, grappled with congregants who had justified bondage through selective biblical interpretation.

Booker T. Washington (1856-1915) embodied the Christian response to freedom's challenges. Born into slavery in Virginia, Washington's family relocated to West Virginia following that state's dramatic secession from Virginia in 1861—a decision largely motivated by differences over slavery and Union loyalty. Washington's educational journey took him from the salt mines of Malden to Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute (now Hampton University), one of the pioneering Historically Black Colleges and Universities established during Reconstruction.

At Hampton, founded in 1868 by Brigadier General Samuel Chapman Armstrong, Washington encountered an educational philosophy that merged Christian principles with practical training. Armstrong, son of Hawaiian missionaries, believed that moral character and manual skills formed the foundation of true education.5 This philosophy profoundly shaped Washington's later leadership at Tuskegee Institute, which he founded in Alabama in 1881 with the mission of educating African Americans for self-sufficiency and economic independence.

Washington's approach reflected a distinctly Christian understanding of human dignity rooted in the imago Dei—all humans bear God's image. Unlike later critics who characterized his accommodationist stance as capitulation, Washington advocated for what he termed "casting down your bucket where you are"—building economic strength and moral character as the foundation for eventual political equality.6 This entrepreneurship is the hallmark of self-governance and financial independence.

Unlikely Allies in the Cause of Justice

The complexity of Reconstruction-era Christianity emerges in unexpected figures like Newton Knight (1829-1922), the Baptist farmer-turned-soldier who led one of the Civil War's most remarkable rebellions. In Jones County, Mississippi, Knight organized what historians call the "Free State of Jones"—a multiracial community that rejected Confederate authority and declared allegiance to the Union.7

Knight's rebellion, rooted in his understanding of Christian equality and opposition to the Confederacy's "rich man's war, poor man's fight," demonstrated how evangelical faith could motivate radical resistance to injustice. After the war, Knight's Republican loyalties and support for Reconstruction earned him appointment as deputy U.S. Marshal for the Southern District in 1872, and later as colonel of the First Infantry Regiment of Jasper County in 1875.8

Knight's story illustrates the theological ferment that emancipation unleashed among white Southern Christians. While many white churches retreated into the "Lost Cause" mythology that romanticized the Confederacy, others like Knight embraced a more honest reading of Christian brotherhood that transcended racial boundaries.

The establishment of Historically Black Colleges and Universities represented one of Reconstruction's most enduring achievements. These institutions, many founded by Christian denominations, created spaces where African American intellectual and spiritual formation could flourish. Howard University, founded by Congregationalists in 1867, produced the "capstone of Negro education." Fisk University, established by the American Missionary Association in 1866, became renowned for the Fisk Jubilee Singers, who introduced African American spirituals to the world.9 Black students were admitted immediately after Hillsdale College’s founding in 1844. The college became the second school in the nation to grant four-year liberal arts degrees to women. These colleges exist because of the prohibitions from established schools. Higher education has always been a competitive landscape where greater freedom and more truth replace biased ideas.

Washington's attendance at Wayland Seminary in Washington, D.C., further shaped his theological worldview. Founded in 1867 by the American Baptist Home Mission Society, Wayland trained African American ministers and teachers in both classical education and practical Christianity. This dual emphasis on spiritual formation and practical service became central to Washington's educational philosophy at Tuskegee.

The Long Arc of Justice

The promise embedded in the Reconstruction Amendments proved, as Martin Luther King Jr. would later observe, like a "promissory note" that America had defaulted upon.10 The legal tender of emancipation required nearly a century to approach fulfillment with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The period between Reconstruction and the modern civil rights movement witnessed the systematic dismantling of many constitutional protections through Jim Crow legislation, sharecropping systems that perpetuated economic bondage, and extralegal violence.

Yet the Christian foundations laid during Reconstruction proved remarkably durable. The black church became the institutional backbone of resistance to racial oppression. The educational institutions founded during this era produced generations of leaders who would eventually challenge segregation in courtrooms, pulpits, and streets across America. This was the model for improvement in Black communities and fostering African American families until Lyndon B. Johnson's Great Society, enacted in the 1960s, which incentivised poverty and miseducation.

Emperor Constantine's leadership initiated Western Civilization, and began the process that Christianity used to shape public policy led us to this point. American Christians during Reconstruction faced the challenge of translating theological conviction into political reality. The Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments represented America's attempt to constitutionally encode Christian principles of human dignity and equality. A legal framework and moral leadership rooted in biblical truth pressed freedom forward.

The witness of figures like Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, and Newton Knight reveals how Christian faith motivated diverse responses to the challenges of freedom. Whether through Douglass's prophetic voice calling America to account for its failures, Washington's patient institution-building, or Knight's armed resistance to injustice, each embodied aspects of Christian discipleship in their historical moment.

As contemporary Americans continue grappling with the responsibilities inherent in our freedom, our history provides both inspiration and caution. Constitutional amendments established a framework for justice, but implementing that framework required sustained moral courage and commitment. The Christian leaders of that era understood that legal emancipation was merely the beginning of a longer journey toward true unity. Today, anyone who sows seeds of division is an enemy of the union that many fought and died to preserve.

Our achievements over the centuries are formidable, and our current aspirations continue to strive for greater justice and peace in this nation. Acknowledging how far America has traveled is important. While we may not see the promised land this side of eternity, we can improve our shared lives today. For Christians committed to the Constantine Doctrine and living out a faith that shapes public life, this history provides a roadmap for continued engagement in the unfinished work of creating a more perfect union rooted in the biblical vision of human value and divine justice.

“It is for freedom that Christ has set us free. Stand firm, then, and do not let yourselves be burdened again by a yoke of slavery (Galatians 5:1).”

General Order No. 3, Headquarters District of Texas, June 19, 1865.

U.S. Constitution, Amendments XIV and XV.

Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution (New York: Harper & Row, 1988).

Frederick Douglass, "What the Black Man Wants," speech delivered in 1865.

Samuel Chapman Armstrong, Memories of Old Hampton (Hampton: Hampton Institute Press, 1909).

Booker T. Washington, Up From Slavery (New York: Doubleday, 1901).

Victoria Bynum, The Free State of Jones (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001).

Newton Knight service records, National Archives.

Joe M. Richardson, Christian Reconstruction: The American Missionary Association and Southern Blacks (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1986).

Martin Luther King Jr., "I Have a Dream," speech delivered August 28, 1963.

https://substack.com/@poetpastor/note/p-163244125?r=5gejob&utm_medium=ios&utm_source=notes-share-action